Going deep (or not)

The analysis of the tawaki dive data we collected at Jackson Head and Milford Sound is largely in dry towels. And the results are pretty interesting.

The GPS data penguins brought home with them already highlighted tremendous differences in the foraging behaviour at both sites. The foraging ranges (that is, the distance the birds travelled during single foraging trips) differed by almost an order of a magnitude, with Jackson Head birds swimming up to 100 km away from their breeding colonies.

In comparison to other crested penguins this is not necessarily record breaking, but still was a lot further than any of the tawaki had travelled in the previous season. At the same time, the ranges of tawaki from Harrison Cove were unbelievably short. The average distance the birds put between themselves and their nest sites was a little above 3 km. Yes, not a typo – three kilometres. These are officially the shortest foraging ranges I have ever heard of in any penguin species!

So, how does that reflect in their diving behaviour and what does it mean?

One could for example assume that penguins that travel a lot show a lower average dive depth compared to birds that hop in the water and start feeding straight away. Why? Well, when trying to cover distances it makes sense to move primarily horizontally which means many shallow dives.

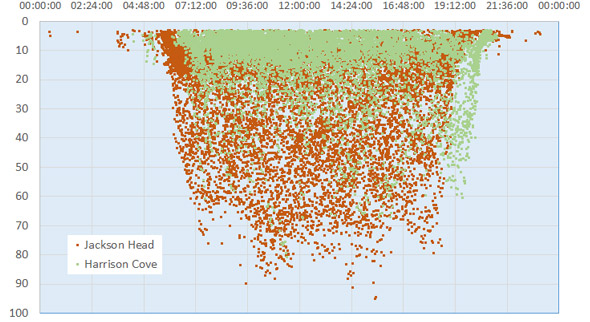

And that’s what we found in the far travelling tawaki from Jackson Head. Almost half of the ca. 13,000 dives recorded in eight penguins were not deeper than 15 metres. The other 6,500 dives went down to depths of up to 90 m, although the majority ranged between 20 and 60m. So that is probably where the penguin were on the lookout for food.

So without having to travel at all… did the Harrison Cove tawaki dive deeper? No, quite the contrary! We recorded about 9,500 dives performed by six birds. And on almost 80% of these the birds stayed in the upper 15 m of the water column. What gives?

Well, underwater visibility in a fiord is quite limited. The fiord is usually covered by a freshwater layer created by heavy rainfalls that also wash a lot of detritus from the surrounding land into the water. As a result you don’t have to go down deep if you want to experience a night dive in broad daylight. This is also why in Milford Sound you can observe deep water species just a few meter below the surface.

For penguins as visually hunters that means that the darker it gets the less likely they are to spot their prey. So it seems to make sense for tawaki to stay up there… until you start to wonder why their prey does not bugger off into the darkness?

Well, perhaps it can’t because the prey the penguins were after was itself looking for food in the sunlit ranges of the fiord. Or the penguin food is brought passively to the surface by water movements. That applies for example to krill – which we found in considerable quantities washed up on the shore and which is a staple food for the tawaki’s closest living relative, the Snares penguin.

Occasionally penguin prey may be found at greater, darker depths. That may be the reason why almost all of the penguins occasionally dove down to 50 m or more. The record for the greatest depth stands at 80.6 m. After we lowered a GoPro into Harrison Cove, we can be sure that at such depths there is not a lot to see anymore.

So what have we learnt?

We have learnt that the Harrison Cove penguins were a lot better off when compared to their Jackson Head counterparts. Not only did they not have to travel to some far away foraging grounds to find food. They also did not have to dive very deep to get to it. In short, foraging at Harrison Cove was pretty damn peachy.

Whereas at Jackson Head, life served the penguins lemons. And admire them for at least trying to make lemonade. The birds did everything they could to raise their chicks. And while it was unsuccessful for many of them, I am sure, next season will see the odds evened out between Jackson Head and Harrison Cove.